Residential mobility in Shanghai

Since the late 1990s, the reform of state enterprises and the growth of the real estate market have led to high residential mobility in the working-class neighborhoods of Shanghai. Through the case of Caoyang city No. 1, urban planner and architect Chen Yang, author of a recent essay on the subject, interviewed two categories of people (native inhabitants and rural migrants) about two main issues: the circumstances of this mobility and its consequences.

Caoyang city No. 1, a community project under the socialist danwei system

The Caoyang quarter is in Putuo district, near the former industrial zone at the west of Shanghai (Puxi). It consists of nine housing estates built successively between 1951 and 1978. Located in the city center, the first city (Caoyang No. 1), with an area of 10.8 hectares, was a flagship project of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) after it came into power in Shanghai in 1949. The 1002 housing project in Caoyang No. 1 was given to the workers of large state enterprises. Most of the native inhabitants were “model workers” (laodong mofan), or even “advanced workers” (xianjin gongzuo zhe), strictly selected from the textile and industry sectors.

From this experimental project, the Shanghai government began to establish a system of public housing (1949-1978) which was financed and built by the state government, subsequently distributed by work units (danwei), and finally managed by the Office of Property Management (BGI). The State was the owner of the housing and the usage rights belonged to the working unit which distributed them free of charge to their employees and workers. The maintenance and rehabilitation of public housing was the responsibility of BGI, to whom the residents paid a modest monthly fee. In Caoyang the inhabitants, who were often colleagues from the same work unit, formed a “community submitted to the danwei system” (danwei zhi shequ); social composition was fairly homogeneous in terms of age, occupation and status. (map of Caoyang)

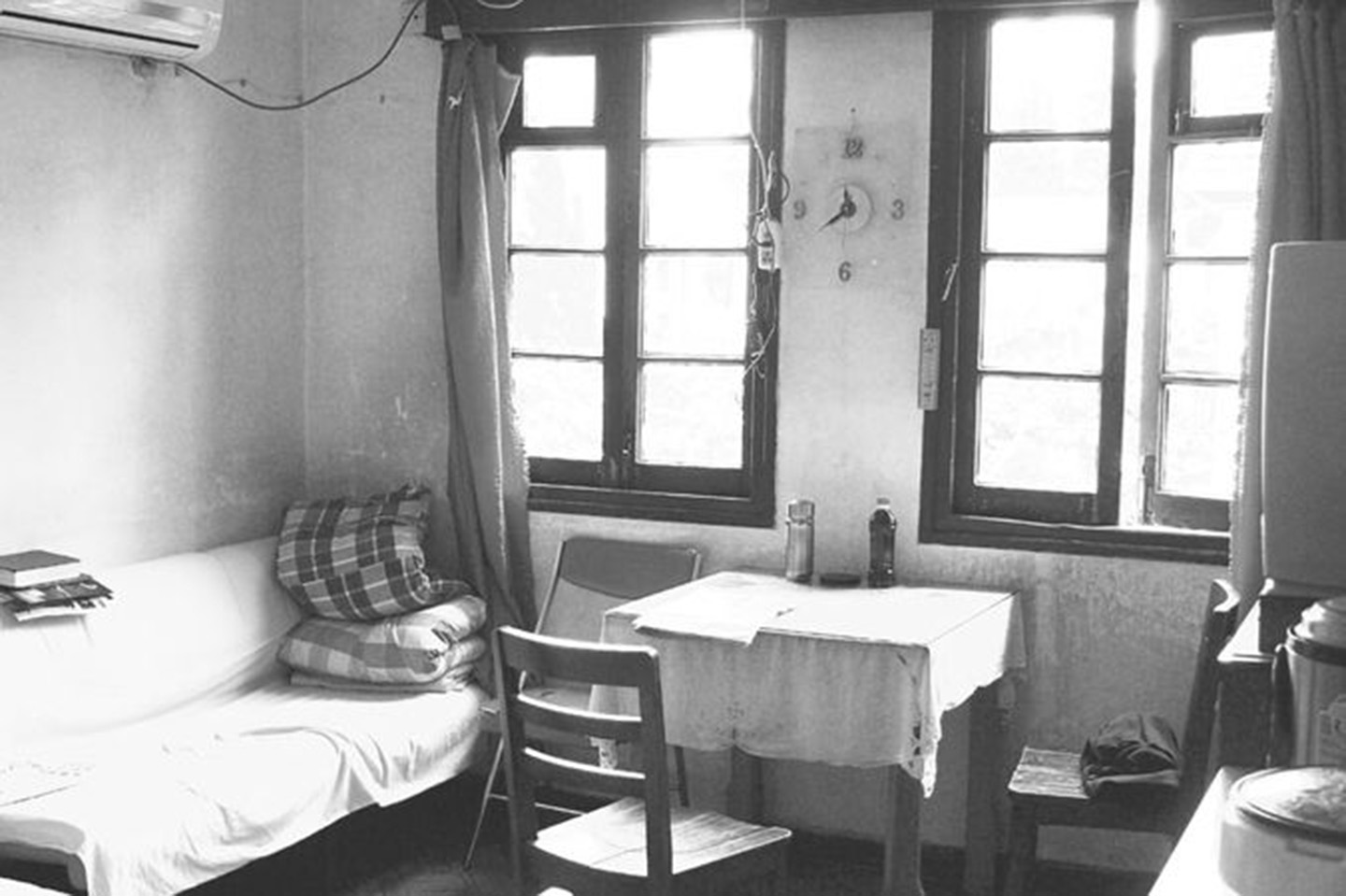

Under the danwei system, residential mobility was low. This can be explained by several factors. First, occupational mobility, the main factor of residential change, was very rare. Moreover, from 1950-1970 in Shanghai, the average area of individual housing was less than 4 m². As a result, such narrow housing could not be easily divided despite the arrival of new generations. In addition, during the socialist era, rather than being considered “property” in today’s terms, property was freely distributed by the local danwei like tradable “goods” between individuals. In this community under the danwei system, the relationship between people and their housing was an extension of the relationship between workers and their work units. Thus, the working class families of Caoyang city No. 1 were subjected to a “double dependency” towards their danwei, which served as both their workplace and their residences.

Caoyang in the new socio-economic context of Shanghai from 1990

The social structure of the danwei system community was disrupted after a series of socio-economic transformations in the 1990s. Foremost among these changes was the reform of State enterprises, which caused the “commodification” of housing and a massive rural exodus. Since the mid-1990s, the reform of State enterprises in Shanghai has caused a sharp rise in unemployment among workers. Caoyang city No. 1, whose inhabitants are largely from industry and textile fields, has been profoundly transformed. The reform caused high job insecurity among the workers as well as a definitive rupture of ties with their work units. However, this break has also given them some professional freedom. Thus the first barrier to residential mobility, dependence on their work unit, was largely lifted. In 1998, the reform of public housing initiated in Shanghai ended the distribution of housing by the danwei and workers were able to buy rights of usufruct on properties previously provided by their work unit. As public housing initiatives became commoditized, many city residents transitioned from being tenants to new “usage rights holders”. The duration of new property contracts, however, still remains limited to 70 years.

While the wealthy families in Caoyang city No. 1 were able to directly buy the usage rights from their work unit, others with less financial means obtained the “right of permanent residence”, a tacit concession offered by the BGI in light of the disintegration of their work unit. Many of the original inhabitants have remained in their original places of residence. If the liquidation of the danwei system and the reform of public housing favored residential mobility in Shanghai, demand in the real estate market however remained very strong due to the influx of migrants from 1990. Rural workers (nongmingong) flocked to Shanghai. According to the annual surveys of the residents’ committee (juwei hui), the population of rural migrants in Caoyang city No. 1 went from 0.9% in 1996 (46 people) to nearly 40% (1,800 people) in 2010, with an annual growth rate of about 27%. As the area of inhabitable space in the city was extremely limited, the increase of the migrant population here can be explained by the fact that many of the original residents left Caoyang city No. 1 during the last decade, further demonstrating their increased demographic and residential mobility.

Survey on social form and social impact of residential mobility in Caoyang City

In June 2010, more than 50 interviews were conducted with families living in Caoyang city No. 1 on two aspects of residential mobility: its circumstances and its consequences.

Residential mobility in Caoyang city No. 1 first appeared with the original inhabitants, who have now largely moved into surrounding city neighborhoods. This spatial proximity allows them to give assistance to friends and family members located back in the city. In addition, these residents frequently keep the hukou registration originally linked to their old addresses. This way, their children are still permitted to attend schools in the area and they will not miss out on any possible compensations resulting from the city’s future renovation. Yet another form of mobility leads to the modification of residential space. For more than half a century, each family in the city has found a way to expand its living space to meet the cohabitation needs of different generations: families on the ground floor changed the space of the courtyard by adding a bathroom or an extra bedroom; residents on the top floors built granaries on the roof; those on the middle floors exploited the corridors and storage spaces. Some families even divided a 12 m² room into 2 rooms. A third aspect of residential mobility is the change of status for some people. According to the 2010 statistics collected by the residents’ committee, about 200 families in Caoyang bought the usage rights to their properties from their work units. Even families who have not acceded to home ownership regret not having taken this opportunity at the beginning of the reform.

As for new residents, few of them have access to buying a home in the city today. This is both due to economic barriers as well as the marketing policy of public housing set up in 1998, which states that “the sale of a house in workers’ housing is reserved only to those with a Shanghai hukou”. In other words, to have the usage rights to a property, rural migrants must first obtain a Shanghai hukou, a major impediment for many migrants. Without one, they cannot change their housing tenure, even if they have the money and occupied their current homes for an extended period of time. The only mode of residential mobility granted to them is “relocation”, which often necessitates a change of job—a requirement that is especially difficult for young rural migrants that may already be in precarious job situations.

Caoyang city No. 1, an area that is well served by public transport with relatively low rents, attracts many migrant workers from poorer provinces such as Anhui, northern Jiangsu, and Jiangxi, as well as those working in the service sector at the bottom of the social ladder. One of the consequences of residential mobility in Caoyang city No. 1 is that the community subjected to the danwei system has gradually become a mixed, heterogeneous, and divided community between original inhabitants and newcomers. The native residents have a predominantly negative attitude towards rural migrants. This attitude can largely be explained by their different habits and lifestyles. The exodus of a segment of the original community in the wake of social reform coincided with the arrival of large numbers of migrants, and as a result, many natives blame the deterioration of environmental quality on new incoming migrant residents. The only way for them to also escape this situation would be to buy or rent a home outside the city, but those who stayed could not afford to buy. To some extent, this feeling of helplessness reinforces their hostility to the new inhabitants.

The difference in language, lifestyle and residence status (hukou) makes it difficult for these new residents to integrate in the local community. Even if they have lived here for more than a decade, they still often fail to build relationships with their Shanghainese neighbors, still considering their homes as temporary abodes, and as such, often do not bother to maintain them.

Conclusion: a fragmented society

Since the late 1990s, the socio-economic reforms and the rural exodus to Shanghai have disrupted Caoyang city No. 1. The relocation of original inhabitants and the arrival of new residents consist of two relatively independent and contemporary processes. The impact of residential mobility did not completely destroy family networks and the old relationships of the neighborhoods. On the contrary, the regression of social and economic status has reinforced the dependence of the original inhabitants to their place of residence. Thus, delocalized residents always keep economic, social and emotional ties with their native city while new residents have difficulties integrating into the micro-society because of the language, lifestyles, precarious jobs, lack of family ties and good neighborliness. The identity of “migrant” is defined by the hukou system, which prevents this population from settling down both physically and psychologically in the city of Caoyang. The first community united by the danwei is beginning to be replaced by a more diverse and dynamic society, but the social and spatial changes have not yet produced a new standard social cohesion.

-

2018/03/09

-

Shanghai

-

Yang Chen

the other map

Explore arrow

arrow

loading map - please wait...