On June 6th, 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China published the latest collection of a long list of Traditional Villages on its website [1]. In total, 6,819 small settlements now boast this title, each one benefiting from a three million Yuan subsidy (440,000 USD) that comes with the nomination.

The list of Chinese Traditional Villages is not the only existing list, as the creation of national records of model villages has become a key feature in domestic practices. There are lists of Historical and Cultural, Ecological, Eco-Civilisation, Beautiful, and Beautiful Leisure villages, to name a few.

Why such attention to villages in China?

Toward a Socialist, Beautiful, Ecological Rural Environment

In recent years, discourses promoting the enhancement and development of villages and small towns have become a recurrent theme all over the world. Whilst certainly part of a global phenomenon, the experience in China presents unique characteristics.

The focus on small Chinese settlements has complex motivations. On the one hand is a longing for rural economic development and improvement of people’s livelihoods; on the other hand, is a desire to acknowledge and promote Chinese culture, and reverse environmental degradation. All these priorities respond to both national and global strategies.

In the past 40 years of reform and opening-up, the coastal cities accomplished their radical development and modernisation process, expanding the national economy but also raising disparities. At the beginning of the 2000s, discontent due to increasing inequalities between rural and urban areas drew the government’s attention. A critical turning point was 2002, with the leadership change from Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao. For the first time, at the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), it was declared that the countryside was key to achieving the national goal of a moderately prosperous society (小康社会) and that socio-economic development should incorporate urban and rural areas alike [2]. Since then, the gaze of the nation has progressively tackled what has been collectively known as the three rural issues (三农问题): agriculture, villages, and farmers. The “unbalanced and inadequate development” has been set as the new national contradiction to be solved, and a clear goal has been laid out: “We must ensure that by the year 2020, all rural residents living below the current poverty line have been lifted out of poverty.” [3]

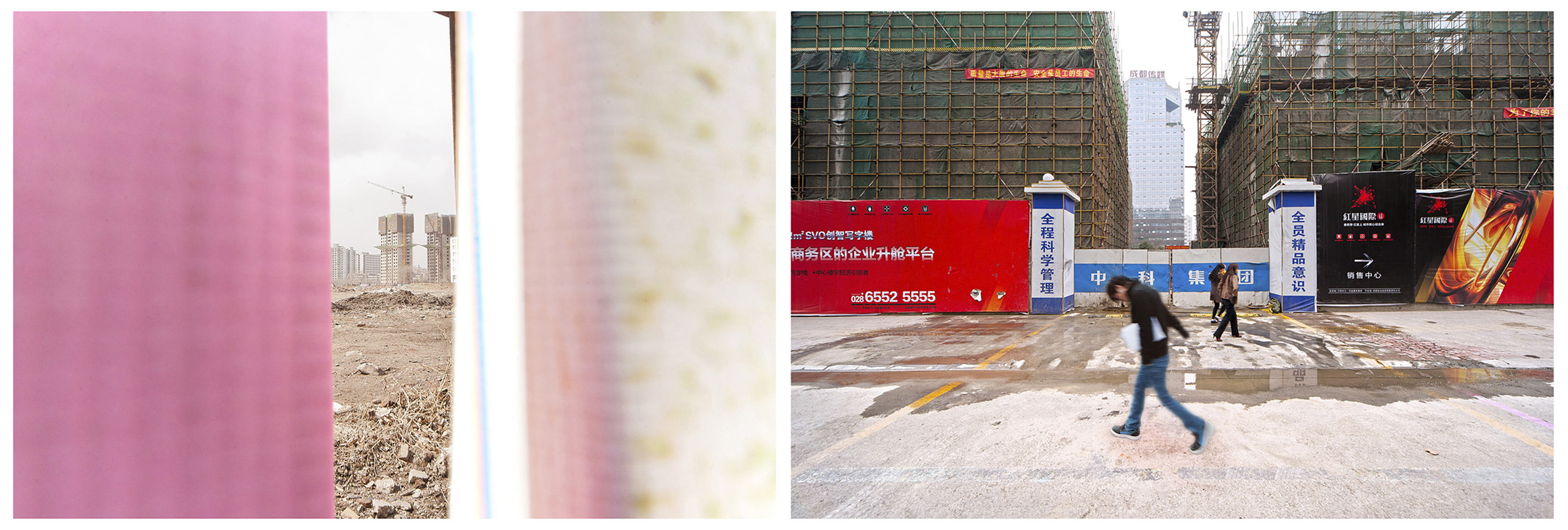

The Chinese development model is closely tied to the urbanisation process, and the law clearly states that “urbanisation is the only way to modernisation” [4]. Thus, the problem of developing rural and marginal areas is an issue of urbanising the countryside (mostly mountainous terrain), and, therefore, the tools proposed to address the imbalance inevitably refer to urban planning criteria. Spatial planning measures have been defined: initially, the approach imposed standard quantitative urban-like models, but in time it has progressively transformed into a more holistic territorial perspective, in which cultural and natural resources contribute to securing a higher quality of development.

At the same time, under the guidance of President Xi Jinping, the role of culture in China has grown at a pace comparable only to its economic development. Culture is deemed crucial in educating the population and gaining international prestige to match the already undisputed financial position of the country. Hence, the official narrative affirms the continuity of a glorious past, emphasising the global relevance of Chinese millenary civilisation.

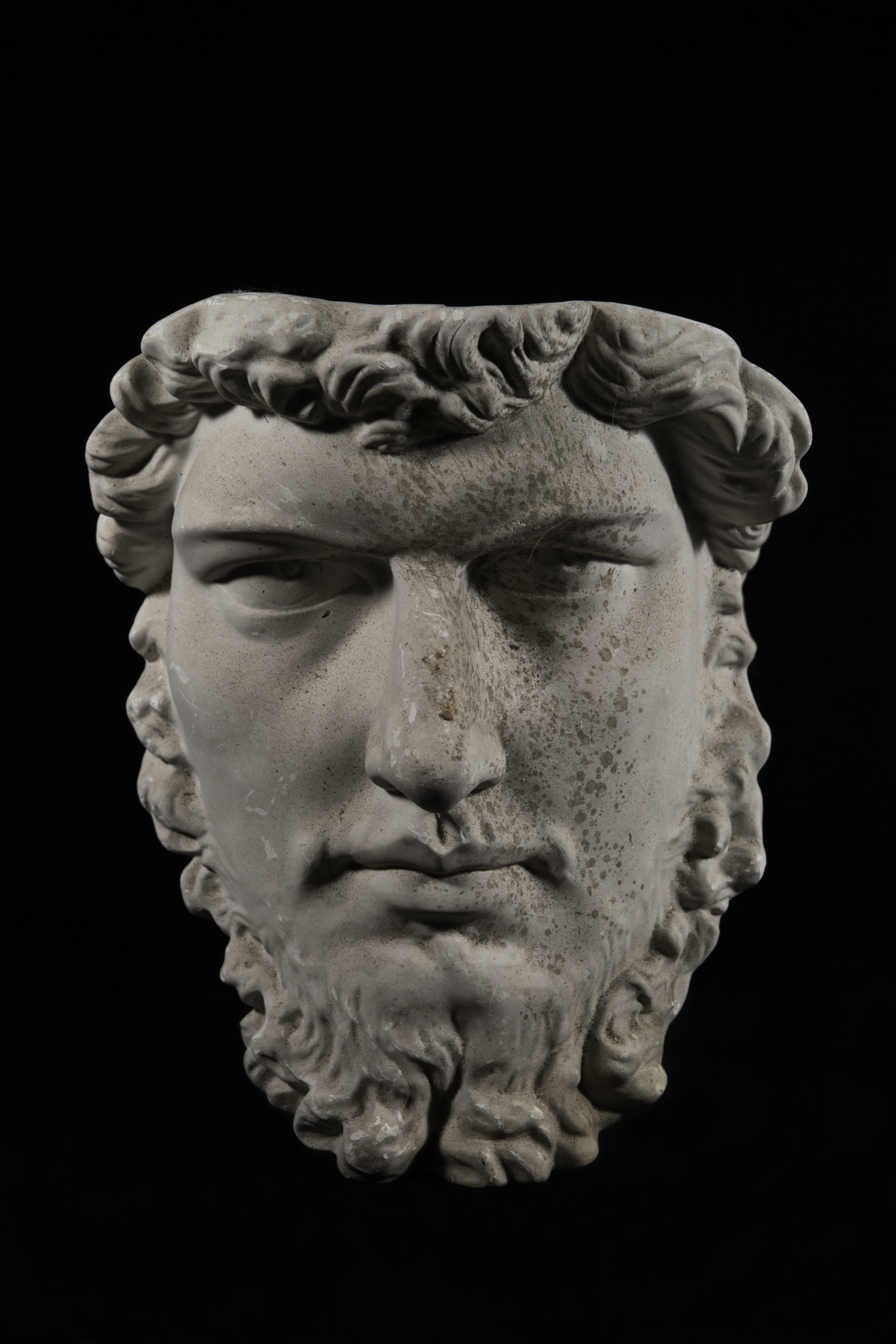

Indeed, the Chinese countryside has played a crucial role in the history of the country, which has been an agricultural empire for millennia. Incredible remnants of this past still mark the land: rural settlements, agricultural terracing, old postal and commercial routes, and hydraulic works. Villages that have escaped radical ideologies and modernisation processes conserve a cultural heritage that is a precious resource for the Beautiful China (美丽中国) promoted by national slogans nowadays. This is especially true for remote villages – usually the poorest ones in a market system – that have remained marginal to historical reversals and transformations.

A further piece to complete this complex yet fascinating picture is the environmental concerns embraced by the government. This new matter has already materialised in a coherent corpus of measures including the establishment of the new Ministry of Ecology and Environment, policies for the protection of eco-systems, environment taxes, and massive investments in renewable energies. Since 2012, when the expression Ecological Civilisation (生态文明) was first officially pronounced, it has become increasingly important in the national discourse and is now the main ideological framework of contemporary Chinese environmental policies, as well as “the most significant Chinese state-initiated imaginary of our global future” [5]. Today, the critical role played by villages, small towns, and their vast surrounding areas is acknowledged as a complementary counterpart to growing cities. China is now developing its own methods of rural revitalisation (乡村振兴) through investing in rural economies as providers of quality environmental services and leisure.

All these policies converge on small settlements and marginal areas: rural economic development, cultural soft power, and the horizon of an ecological civilisation.

Urban planning measures

Planning strategies began operation by rationalising villages and regional layout. Scattered villages merged into larger and more compact settlements through the demolition of hamlets, relocation of villagers, and consolidation of primary farmland. Governmental campaigns called for the rapid provision of essential infrastructure and public facilities including roads, power grid, telecommunications, sewerage, waste collection, schools, health clinics, post offices, etc. (according to the 2006 strategy Building a New Socialist Countryside, 社会主义新农村建设).

In 2007, the Urban Planning Law became the Urban and Rural Planning Law (城乡规划法), and for the first time, every administrative village was required to formulate a 20-year master plan for redevelopment. Furthermore, an urban-rural integration strategy was put forward, incorporating rural territory into the spatial planning regime [6]. Provinces were asked to define strategic regional plans, outlining the relationships among settlements of different sizes. Small inland cities were planned to become centres for networks of smaller settlements and clusters of villages, providing the services which marginal areas lack.

The role of the heritage and the tourism lever

In the span of a few years, the interest in the cultural and natural aspects of villages and rural areas has steadily grown. The heritage narrative, based on contemporary national needs, has been reconceptualised to broaden its scope and fit the priority of poverty eradication [7].

Thus, the Chinese approach to rural heritage remains focused on tourism promotion to meet the need for rapid development. It is no coincidence that in March 2018, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism was established through merging two formerly separate entities, the Ministry of Culture and China National Tourism Administration. Tourism is considered a means to fight poverty by redistributing private resources from coastal cities to inland regions. A list of Beautiful Leisure Villages (中国美丽休闲乡村) and experimental zones for Rural Tourism, established by the Ministry of Agriculture, pioneered this strategy and recently, at the end of July 2019, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism launched a further group of Key Rural Tourism Villages (全国乡村旅游重点村名单). In remote, rural, and ethnic regions, tourism is introduced as a modernising tool to promote social and cultural development and to better integrate minorities within the nation-state [8]. Large-scale tourism investment companies are invited to act as engines of rural development, but this strategy often results in homologated models of intervention, with little benefits for the inhabitants and potential controversial effects that have generated tensions with local communities in the past.

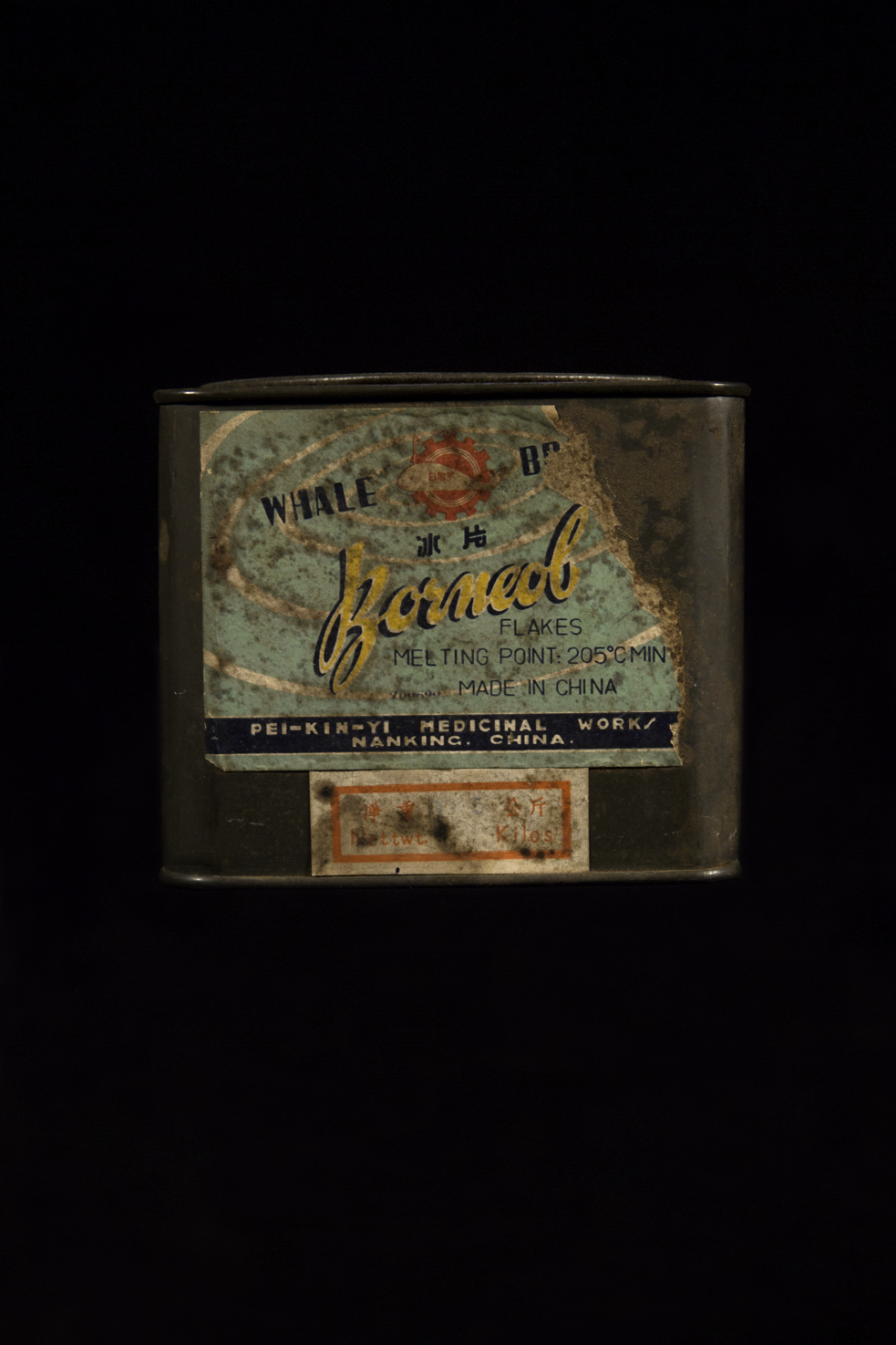

Beyond tourism, the attention to the countryside and the increasing importance of culture and environment have favoured a shift in the way villages are valued, leading to a substantial leap forward in the heritage discourse. As a result, the rural legacy has been identified in a larger body of elements: heritage is no longer limited to monuments or unique pieces of architecture, instead extending to urban fabrics, landscapes, and complex environmental systems, encompassing spatial arrangements, agricultural practices, social structures, construction technologies, and philosophies of life. All these attributes have been incorporated into official discourses, local policies, and planning mechanisms that are now beginning to be implemented.

Ever-greater numbers of villages are being included in lists for their promotion and enhancement.

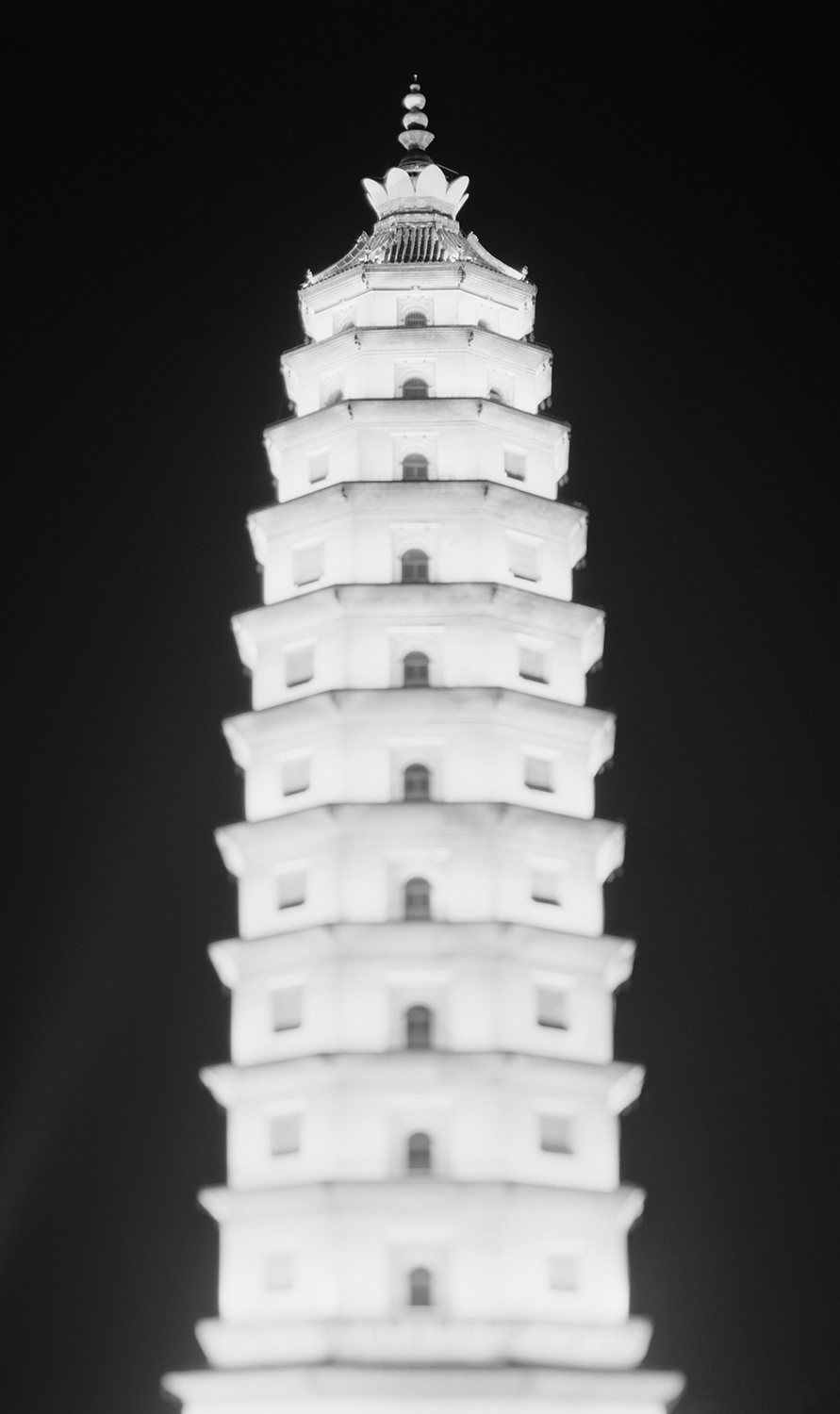

In 2000, two small settlements in southern Anhui Province, Hongcun and Xidi, were declared World Heritage Sites [9]. The event was a pivotal moment, as it was the first time that the historical and cultural value of a village in China was recognised at such a level.

In 2003, the first record of Chinese Historic and Cultural Villages (中国历史文化名镇和村) was published, its contents including settlements boasting relevant historical architecture. The list of Traditional Villages (中国传统村落) followed in 2012. This new list expanded the scope of the earlier group by promoting a higher number of settlements, based on the rationale that “although some villages might not have many ancient buildings, they embody, in their layout, in their location, and many intangible aspects, the cultural elements that reflect the essence of Chinese culture” [10]. Protecting the heritage of these villages is declared to be a means for enhancing the awareness and confidence in the value of Chinese culture, promoting the multiplicity and diversity of Chinese cultural expressions (including all officially identified ethnic groups), and leading the economic development of rural areas. Respective of the fact that the country is “a thousand years old farming civilisation, and traditional villages have preserved the cultural roots that stemmed from the countryside” [11], the Traditional Villages list conveys an idea of heritage drawn on this specific interpretation of Chinese ‘farming’ culture, and is finalised to create a vision for the future in continuity with its rural past.

A new environmental perspective

Parallel to the focus on culture, the attention to nature is represented by the Ecological Villages (国家级生态村) list created by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2006, and in its updated version the 2014 Eco-Civilisation Villages list (国家生态文明建设示范村). These lists integrate concepts of environmental protection with China’s rural culture to address a new model of urbanisation focused on the nexus between villages, agriculture, and rural landscape. The heritage of farming culture is considered an asset to ensure food security and high-quality products. It has the potential to lead the shift from an economy of subsistence to one based on commercial exchanges while helping the preservation of rural landscapes and ecological environments.

At the same time, the growing number of listed settlements has drawn attention to the specificities of traditional rural settlements, especially in terms of regional and local characteristics and ethnic expressions (as many ethnic minorities reside in remote villages). China is a vast territory with a multitude of landforms and regional climates where diverse cultures have developed a rich range of agricultural patterns and different settlement models. Consequently, since 2014, national planning tools have incorporated an approach encouraging customised planning interventions that take into account distinctive natural, geographical, historical, and cultural conditions to avoid the homologation of practices (National New Urbanisation Plan 2014–2020).

The lists of model villages were conceived independently from each other and are managed, individually or jointly, by different government departments (e.g. Ministry of Housing and Urban-rural Development, Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Ecology and Environment). They also respond to diverse scopes such as infrastructural and agricultural modernisation, heritage preservation, tourism promotion, environmental improvement. Yet, regarded together, they can be considered pieces of a much more comprehensive strategy based on a holistic idea of territory (eco-system), in which cultural, historical, and natural components are mobilised in efforts of rural revitalisation, looking for a way to secure a better quality of life for all–urban and rural–Chinese citizens.

Notes

[1] http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201906/t20190620_240922.html

[2] Ye, Xingqing. 2009. “China’s Urban-Rural Integration Policies,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 38 (4): 117-143.

[3] Xi, Jinping. 2017. Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

[4] The State Council of the P.R. of China. 2014. 国家新型城镇化规划 [National New Urban Planning 2014-2020], Beijing.

[5] Hansen, Mette Halskov, Hongtao Li, Rune Svarverud. 2018. “Ecological civilization: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future”. Global Environmental Change 53 (2018) 195-203.

[6] Bray, David. 2013. “Urban Planning Goes Rural: Conceptualizing the ‘New Village’.” China Perspectives 2013 (3): 53–62.

[7] Lincoln, Toby, and Rebecca Madgin. 2018. “The Inherent Malleability of Heritage: Creating China’s Beautiful Villages”. International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (1): 1–16.

[8] Cornet, Candice. 2015. “Tourism Development and Resistance in China”. Annals of Tourism Research 52: 29–43.

[9] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1002

[10] The State Council Information Office of the PRC (SCIO). 2013. 国新办举行改善农村人居环境工作等情况发布会 [The State Council Information Office Held a Press Conference on the Improvement of Rural Living Environment], Beijing (translation by the author).

[11] Ibid